Set on the isle of Rousay in 1898, it tells of the chance discovery of a

prehistoric grave chamber in a thunderstorm. In the end, the narrator walks

home with a skull in her basket.Above

all, this is an excavation report, not a work of fiction.

|

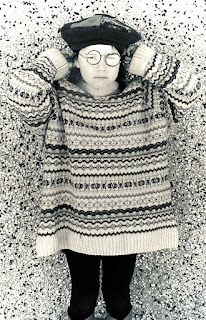

| Eliza D'Oyly Traill Burroughs (1849-1908) (GB241/L3295/4) |

The

author (and 1st-person narrator) is Eliza D’Oyly Traill Burroughs

(née Geddes, 1849-1908; pictured), and the document is mostly known as ‘the

journal of Lady Burroughs’.The

manuscript, however, does not form part of a personal diary; it comprises nine

loose pages and drawings that are solely focused on the discovery and the

ensuing excavation of Taversoe Tuick – which is why it is referred to as a

‘report’ and a ‘manuscript’ here, rather than a ‘journal’.

It

is a lively piece, full of riveting questions and theories about prehistory,

glimpses of Eliza’s observational sense of humour and her emotional

intelligence, as well as dramatic descriptions of the storm-swept island of

Rousay.

Eliza’s

writing style creates a personal connection between herself and the reader: she

makes no secret out of the joy she got from the discovery, recommending

excavation to “anyone in search of excitement!” She also gives

insightful remarks about the moods of those present (her husband and two

workmen) – in addition to providing measurements, detailed site descriptions,

and sketches.

The

report remained an unpublished manuscript until Diana Reynolds transcribed it for PSAS in 1985 – but even after

that, Eliza herself remained a little-known figure in Orkney history, usually

overshadowed by the history of her husband, Lt-Gen Sir Frederick W Traill

Burroughs, the laird of Rousay and Wyre (see ‘further reading’, below for more

information on him).

I

came across the Taversoe Tuick report years ago when I was looking for case

studies during research into Orcadian archaeology and folklore (I won’t

digress). Having discovered a new favourite author, I began to search for Eliza

– Who was she? What else had she written? Who had written about her? – only to

find… well, not very much.

Initial online searches did not even

reveal her birthdate (9 May 1849).

|

| Lady Burroughs (Ref: GB241/S18/1) |

I

soon realised that if I wanted to read more by her, I would have to dig deep

for it – and if I wanted to read more about her… I would have to write

it myself (spoiler alert: I have!).

Over

the years I would find out that Eliza was the first person to bring cinema to

the isle of Rousay (in 1901), that she promoted local craftwork and artistic

talent, took a deep interest in the welfare of local schoolchildren, knew May

Morris, liked the outdoors, enjoyed stargazing, and was partial to tea.

Still

– to this day I have not found any private letters or diaries that would

provide a clearer idea of her personality and her views (other than her

archaeological views).

In

photographs (of which there are many), she has a confident, intelligent expression

(her writing style and attention to detail would support this), but photographs

are mere moments in time. At present, hers could still do with more context

Back

in 2017, my first starting point was the Orkney Library & Archive (OA), Archon code GB241

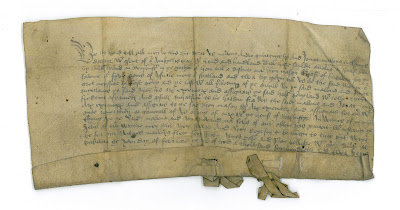

Apart from Eliza’s original report (GB241/D19/10/9),

many of the relevant sources were 19th-century newspaper clippings (the

OA’s D19 papers; I also consulted the British Newspaper Archive), and while I read these

with interest, the warning words of Dr Samuel Johnson (1709 - 1784) resounded

in my mind: in his periodical the Rambler (nr. 60, 13 October 1750), he notes that many writers

rely too heavily on newspaper articles to piece together a biography of their

subject, when, in fact:

“

(…) more knowledge may be gained of a man's real character, by a short

conversation with one of his servants, than from a formal and studied

narrative (…)”.

|

Dr Samuel Johnston (1709-1784), noted biographer (among many other works)

Painting by Joshua Reynolds |

For

obvious reasons, this is not something I could do. Eliza, her household staff,

and I are separated by more than a century. We have walked the same ground, but

not at the same time.

This venture was impossible after all.

Or so I thought!

The

OA Sound Archive holds a recorded interview with Alexina Craigie (OSA/TA/149). Alexina

Craigie had worked at Trumland House around the turn of the century and was

still alive in 1977 (!) when Howie Firth interviewed her for Radio Orkney.

The

interview is on a reel-to-reel tape, and I was quite apprehensive the first

time I used it. Not daring to press any buttons for fear of breaking things, I listened

to the interview in one go once it had been switched on by one of the

archivists.

|

| Ye Olde Reel-to-Reel Tape Player |

The

interview is a treasure trove of anecdotes, memories, and descriptions of

Orkney, with focus on Rousay. It contains stories and recollections about Alexina

Craigie’s own family and memories that were told to her by her relatives.

The

scope of history on the tape easily goes back at least into the early 1800s, if

not before that, with tales of press gangs, peat cutting, the development of a

postal service in Rousay, hazardous whaling trips, and the kinds of foods that

were eaten in Rousay when Alexina was young.

Alexina’s

memories of working at Trumland House are a relatively small part of the

interview, but the anecdotes she does share have been invaluable for my

research, especially as they give an insight into Eliza’s character by someone

who knew her personally.

These

anecdotes include Eliza wandering about Trumland House looking for company (and

tea) while her husband and houseguests are out; and Eliza giving up her seat in

a cart between Westness and Trumland, deciding to walk instead, which saved

Alexina a 3.5-mile trek while on duty.

In

summer 2018, I was back in Orkney and had arranged with the OA to transcribe

the interview. My concerns regarding the age and fragility of the tape (which

had prevented me from pressing any buttons previously) had turned into a plan

to commit the words of the interview to paper (or, to be more precise, to pdf:

GB241/OSA-TA-149).

The

interview lasts for about 30 minutes and I set aside two days for the

transcription. This included listening to the recording various times until I

became familiar with the melody and rhythm of Alexina’s voice and her manners

of speaking, before writing it up bit-by-bit.

Finally,

I listened to the tape several more times, while reading and correcting what I

had written up until every word matched (to the best of my understanding).

At

this point, let me emphasise how much help I had from Colin Rendall (Orkney Archive Technician) during those days.

His advice was crucial, as I wanted to avoid mistakes out of ignorance,

especially when it came to dialect and vernacular ways of phrasing (interesting

detour: I learned that there is no such thing as ‘the Orkney dialect’, as every

island of the archipelago has their own).

To

my understanding, the role of the transcriber is just that: to transcribe every

spoken word, not to correct anything – be it dates, place names, historical

facts – nor to smooth over any phrasing (although some transcribers choose to

omit fill noises; for example, if the speaker says ‘erm’ many times – which

Alexina does not).

Of

course, even a transcription comes with its own bias (and therefore

responsibility!) – simply because it is carried out by a person, who is making

decisions throughout the process. This is an important point, but it would need

its own discussion.

The

(largely) passive part I played as a transcriber was what made the process even

more interesting. I was not putting together a polished, reviewed history. Instead,

I was recording a private person’s memory and understanding of the time she lived

in, and her own life story embedded in that.

Above

all, listening to the voice of someone who was alive during the 19th

century (!) felt like a rare privilege. Unfortunately, a written transcription

does not record the sound of someone’s voice, nor their gestures or facial expressions

while they are speaking. These are the first elements to become (apologies in

advance…) ‘lost in transcription’.

Alexina

Craigie’s voice is clear and strong (she was about a century old at the time of

the interview!), her phrasing elegant. The tone of her voice reveals a bright,

friendly sense of humour during some anecdotes, while hinting at a profound

loyalty to those around her in other parts.

When

she begins to talk about Eliza, you can hear how her face lights up with a

smile. It is clear from her voice alone that she got along well with her, which

adds even more weight and meaning when she speaks affectionately about Eliza:

“Lady

Burroughs was… oh my gosh… [inaudible], she was the most humble lady in many

ways (…). You couldn’t imagine!”

|

| Alexina Craigie (1879-1980) Photographed in 1975 (GB241/L2238/2) |

There

were words – sometimes entire phrases – neither Colin nor I were sure about,

which I have either marked with ‘inaudible’ or provided two possible options

for (not ideal – but I felt this was preferable to putting words into the mouth

of the speaker). Hopefully I will be able to fill in those gaps and update the

transcription sometime.

I

could not have done this transcription without Colin’s help, and I am very

grateful not only for his advice and proofreading, but also for all the cheerful

banter and coffee. Those two days were a joy.

This

is the closest I could ever hope to get to “having a short conversation with

one of [Eliza’s] servants” (or at least eavesdropping on one!) as a

means of gathering biographical information. I hope Dr Johnson would let me off

the hook.

“There

is no Answer from the Unrecorded Past”, Eliza notes while trying to make sense

of Taversoe Tuick.

In

my case, this applies to ‘answers’ that were once recorded in writing

(unlike the prehistoric remains Eliza dealt with) but have become (apologies

again…) ‘un-recorded’ by being lost, thrown out or destroyed.

By

transcribing and digitising we can delay the loss of people’s life stories and

keep them available for another few generations.

I

look forward to being back in Kirkwall again soon and visit the Orkney Archive. Maybe I

will be able to fill in some of those ‘inaudible’ gaps.

On

a final note: My

research into the life of Lady Burroughs is far from complete. I would very

much like to hear from you if you know of anything relating to her. Be

it an ancestral connection, letter/s, photograph/s, a diary (one can but hope!),

or even just a brief anecdote you think you heard somewhere. Nothing is

irrelevant!

I

have also tried to track down some of her original watercolours, but to little

avail so far. Everything – however small, however brief, however anecdotal – is

of interest!

You can contact me

(Nela) at: ForgottenStories@socantscot.org

A short film

portraying the storm-swept discovery of Taversoe Tuick will be shown at this

year's Orkney Storytelling Festival. This film forms part of

the Forgotten Stories project.

Further

reading:

Nela’s article

about Lady Burroughs:

Scholma-Mason, N M A (2021),

‘Eliza D’Oyly Traill Burroughs (1849-1908): A Voice from the Unrecorded Past’

in Proc Soc Antiq Scot 150, 279-299. https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.150.1317

This

paper was awarded the R B K Stevenson Award 2021

Hard copies of this article and Diana Reynolds' article are available to read in the Orkney Room (Orkney Room Periodicals, 941, PSAS, Volumes 115 and 150)

William Thomson’s

biography of Lt-Gen Sir F W Traill Burroughs:

Thomson, W P L (1981) The

Little General and the Rousay Crofters: Crisis and Conflict on an Orkney Estate.

Edinburgh: John Donald.

(A copy of this book is available to read in the Orkney Room 333 Y)

Alexina Craigie's Interview

Howie Firth’s interview

with Alexina Craigie (1977) can be found in the Orkney Sound Archive under GB241/OSA/TA/149.

Nela Scholma-Mason’s transcription

(2018) of this interview can be found under: GB241/OSA-TA-149 in the Orkney Archive

.png)

.png)

.png)