Continued from yesterday. Researched and written by guest blogger Fiona Sanderson:

‘Finding Dr Garvie’ and reconstructing the photographs.

For my next visit to the school, I had borrowed some costumes from the local drama club, and sent them ahead on the boat. I arrived to find the children playing a favourite game around the school, which was to hide a thumb-sized cutout of Dr Garvie for the others to find. They were excellent at finding very tricky hiding places! As I joined in, I realised that this was the same game I had been playing since this research project began.

Once we had loaded up the kelp barrow with the costumes for the day, we were off along the shore to reconstruct one of Dr Garvie’s pictures.

Robin directed the photo shoot, including location management, and a bit of kelp pit rebuilding. The day was also made possible by Louis Craigie, who was happy to appear in costume too. And Phoebe made a great job of being Dr Garvie herself.

It was a perfect day, with lots of the best kinds of learning.

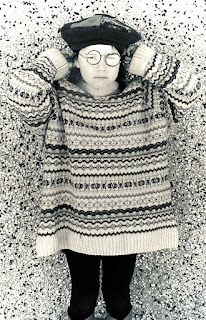

Sinclair Scott came to talk to us about his early memories of growing up on the island. Here he is with a copy of Dr Garvie’s photo of him as a baby.

|

| Sinclair Scott with his photo at ten months old, taken by Dr Garvie |

I explained that the films would have been sent away to be developed and then printed, and that this might have taken a while, especially in winter, if the boat was delayed. One of the children commented ‘that means that baby night have waited months to see what he looked like!’

So, that’s what’s been happening on the island. Meanwhile, there have been some other exciting developments.

I was continuing to work with Beatrice Thomson, captioning all of the Garvie photographs from North Ronaldsay; more than 500 of them. It’s not always possible to tell who and where the photographs were taken, but with patience and cross referencing, we are getting there. Many interesting stories later, we have now completed the first draft of the captions, and are working on the finished document.

That kind of close-looking also reveals more and more.

I noticed the pinnie fabrics that the women were wearing. Bright and colourful, perhaps put on especially for the photograph, there was a whole world of pinnies that I hadn’t been aware of. I realised that these garments are often overlooked, although they would have been important as practical work garments, and, through choice of pattern and style, an important means of self expression too.

Then, one day, I noticed a tiny shadow of a camera, in a group shot that included Beatrice Garvie…. The first clue to the actual camera that she used… Could I somehow identify it?

Further, I had come across a tantalising ‘Garvie’ post on an ‘Ancestry’ website… a living Garvie! I sent a message out into the ether, and hoped that this would be a Garvie family member who would want to respond.

Time passed.

In a marvellous rush of events, all the detective work began to find its reward.

‘Strong, forthright, cantankerous’

First, a great niece of Dr Garvie got in touch, and agreed to have a conversation on Zoom. Three generations of them came along! The Zoom screen was a mosaic of Garvie genes.

They told me they knew very little of their great aunt, other than that she was a doctor, and that they had never met.

I was delighted that they were so intrigued to hear about her Orkney connections, to hear some of what I had discovered, to learn that she had been a photographer, and to actually see some of her work.

I described what I had learned about her from Ann Marwick’s peerless sound recordings, and from islanders’ recollections of her; and asked, did she sound like a typical Garvie? ‘Yes’ came the reply from Grace; ‘Strong, forthright, cantankerous, she would have fitted right in!’.

Spreading the word

It began to feel like it was time to spread the word of this story further, and I was unsure of what to do next. I felt really proud of the work I had done, particularly what had happened with the school on the island. But I knew that the quality of the photographs needed greater recognition, and the story of her life did feel too remarkable for it not to be known. And what if, by spreading the word, it might be that other collections of her work beyond North Ronaldsay might appear?

I first showcased some of the photographs in ‘Holm Sound’, a series of Orkney based online broadcasts.

Then, there was an opportunity to take part in a podcast series, called ‘Unforgotten Highland Women’. This positioned her alongside a diverse set of very remarkable women. It also gave me some good practice at telling the story so far.

It felt essential that the Garvie family should be there, as well as the school, to share the story from their own perspectives, and Lucy from the Orkney Archive had also agreed to join in. This podcast will air sometime early in 2023.

At one point in the podcast, I showed the photo in which Dr Garvie is holding her camera. Sharon Elliott, the twice great niece of Dr. Garvie said, ‘I’ve got a surprise’.

She brought out a Voigtlander ‘Brilliant’ camera that had belonged to her Great Grandfather.

|

| Sharon reveals a camera from her family’s collection |

There it was. An unmistakable match. Dr Garvie may have used more than one kind of camera in her work, but here was a definite ID of the one she is holding in this picture.

I was very happy with that outcome, as in months of searching for 1930s cameras online, and despite the help of local photographers, I had got nowhere.

The Voigtlander ‘Brilliant’ camera was a very popular model in the 1930s. The most basic model had just three settings each for focus, aperture and shutter speed. The ‘Compur’ which is I think the one used by Dr Garvie, is a little more sophisticated, allowing for more successful hand held photography, since the shutter speeds are faster.

|

| Close-up of Dr Garvie with camera |

With Colin’s help, from the Archive, I’ve been learning to use these cameras, and now have three in working condition. I’m looking forward to using them in the next stage of this project. Wouldn’t it be great to get those cameras taking pictures back on North Ronaldsay?

They had a first outing very recently, when Fenella and Fiona, sisters in the Garvie family, and great nieces of Beatrice, came up to visit Orkney. They met with Beatrice Thomson, the archivists who have been involved in the story so far, and with myself. We spent an afternoon looking through the Dr Garvie photo albums, and then Colin took us all outside to record the visit on the Voigtlander.

It felt like a very satisfying completion.

Finally, another very pleasing outcome: An enquiry from Dr. Jenny Brownrigg, exhibition curator at the Glasgow School of Art. She said she was putting together an exhibition of ‘Scottish Women Photographers’, and hoped to come to the Orkney Archive to see the Beatrice Garvie photographs with a view to her inclusion in the exhibition.

This exhibition is called ‘Glean: Early twentieth century women film makers and photographers’, it takes place at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh, between November 2022 and March 2023.

Jenny Brownrigg’s estimation of the quality of Dr Garvie’s photographic work was wonderful to hear. She gave me insights into the strength of her camera work, particularly the capturing of movement, and her noticing of form in her composition.

She also gave me more of a context to understand the work, given that many of the women photographers of the time would have come from very privileged backgrounds, and had independent means. Dr Garvie was singular in ‘paying her own way’.

Jenny Brownrigg agreed it was likely that Dr Garvie was an experienced photographer before she came to the island. A clue to this is found in the print marks on the back of her photographs, that show she used a place in Oxford to develop her work.

|

| Print mark on the reverse of the Dr Garvie photographs. |

This suggests that she may have begun taking photographs when she was working in England. So, it’s probable that she did produce work elsewhere. Perhaps, somewhere, someone who has come across this story, is already dusting off a box of old albums

With

thanks to Colin, Lucy, Andrea, Sarah and Vikki at the Archive, to Ellen Pesci who

facilitated loans of the medicine chest and camera from the Tankerness House

Museum, to Beatrice Thomson, everyone at North Ronaldsay school and to Rebecca Marr for camera loan and ongoing camera advice.